Christine Sun Kim Explains Her Site-Responsive Project

Clip: Season 11 Episode 3 | 1m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

A muralist paints Christine Sun Kim’s work “Time Owes Me Rest Again” at the Queens Museum.

As a muralist paints artist Christine Sun Kim’s site-responsive project at the Queens Museum, “Time Owes Me Rest Again,” Kim explains the ideas behind the piece. She used echoing motion lines to represent the five words in the title in American Sign Language, conveying the unease and fatigue many felt during the COVID-19 pandemic and the persisting inequity between Deaf and hearing communities.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Christine Sun Kim Explains Her Site-Responsive Project

Clip: Season 11 Episode 3 | 1m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

As a muralist paints artist Christine Sun Kim’s site-responsive project at the Queens Museum, “Time Owes Me Rest Again,” Kim explains the ideas behind the piece. She used echoing motion lines to represent the five words in the title in American Sign Language, conveying the unease and fatigue many felt during the COVID-19 pandemic and the persisting inequity between Deaf and hearing communities.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch ART21

ART21 is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Everyday Icons

Learn more about the artists featured in "Everyday Icons," see discussion questions, a glossary, and more.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪soft pensive music♪ Lately, I've been into motion lines.

♪♪ You can find those in comic strips or comic books.

And I thought they were a perfect reflection of sign language, and how it carries a lot of weight and emotion.

For example, the sign for time: I tap my wrist with my index finger.

I looked at a bunch of different signs that come into contact with the body, and I came up with a one-line poem to fit the current climate and what was happening in this area.

♪♪ "Time owes me rest again."

[woman] Yeah, maybe you can shave a little bit.

Yeah, bottom, bottom part.

[interpreter VO] This experience made me think I can work with such a large scale; I thought a lot about that.

And it felt right that maybe this is the best way where we can shove or force our deafness or our existence or our deaf voice, and do that in their everyday lives, in their everyday space.

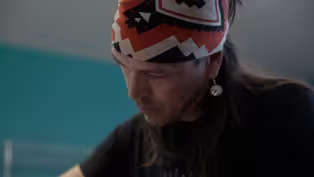

There's a tendency to perpetuate this romantic, There's a tendency to perpetuate this romantic, historical narrative of Native people, which is, "This is primitive, this is ancient, this is not present."

And so I started a whole series of projects that were called -- and it's kind of an ongoing set of ideas -- but it's called Future Ancestral Technology.

It's science fiction, it's speculative fiction.

It's imagining what and how our culture shifts and changes into the future.

♪airy ethereal music♪ And if it's hard to express what it means to be Indigenous today, what does it look like if I bypass today and consider what it means to be in a distant future?

♪♪ So, like, all of the stuff that we're using right now is gonna be around for a while, sitting in landfills.

And rather than recycling it and turning it into new products, I'm like, "What do we do if we just transform this material?"

[Cannupa] These are, like, hockey gloves.

This is an old crochet blanket.

I maintain a hunter-gatherer practice in the 21st century, but the fields that I navigate are different.

All of the wool that I get secondhand, it's leftover.

So, there's very few things in the making of any of this work that is dependent on firsthand manufacturing.

Any time I go to a thrift store, if they've got an Afghan and I like its kind of color story, I will dive in, and...

It's like navigating the detritus of America.

And it's important to tell these stories for future generations because a lot of Indigenous cosmology is based on sustainability.

Like, "You are an extension of the land, you belong to the land."

Could I imagine a future where we all understood that collectively?

A protest in North Dakota against a major oil pipeline continues to grow.

Over 100 Native-American tribes have joined the fight against the project, saying that it threatens one tribe's water supply and its sacred land.

[Cannupa VO] In Standing Rock, it was described as "protest," but the reality of that situation was... everybody who came there was standing to protect water more than against oil.

Seeing a riot police line, the gear that they wear is just completely dehumanizing.

And so, I was inspired by civil unrest that unfolded in Ukraine, where people were bringing mirrors to the front line so that the police could see themselves.

I went to a hardware store, and designed and made these mirrored shields in the parking lot, and made a video to show how to make them.

♪energetic inspiring music♪ The main thing is that it's an empathetic response to violence.

♪♪ At the time that we were bringing, like, 500 shields into Standing Rock, the police and these private security forces, they were confiscating anything that could be considered a weapon.

And we decided that the best way to hide these pieces was to utilize my privilege as an artist.

♪♪ And we were like, "No, these aren't shields.

It's just an art piece."

[footsteps in gravel] Mm.

There were antelope horns on this piece, and I think I locked moisture in, and they exploded.

The unfortunate thing is... they fell on some of my sons' work.

My oldest boy, 'io, made this little guy.

He says it's a monkey.

And my youngest, we've got this...

I don't know, it looks like a Texas toast hamburger with a face on it?

And here's my spider head.

♪sparse ethereal music♪ Oh, here's the fam.

Hey, boys!

[Ginger VO] During the pandemic, everything shut down.

Before that, Cannupa was traveling, like, 80, 90 percent of the time, and it wasn't sustainable.

Thanks, guys!

I don't know where my art practice is different than my life, and they're a part of my life.

Hey, if you guys want to make something alongside me, you can go grab some clay out of my studio.

[Ginger VO] This past year, we've been traveling with our whole family.

[Cannupa VO] We homeschool our children -- had been homeschooling them even prior to the pandemic.

Bringing them along on these trips is an important part of their education.

And we thought that doing that would create a healthier bond with all of us.

[Cannupa] What do they say?

"You've got to get your own house in order... [chuckling] before you start telling somebody else to clean up."

♪♪ I have a hard time with the title of "artist," you know?

Like, that's what you do.

That's who you are; you're an artist.

You are what you do, right?

So I'm an artist, because I make art.

And I'm like, "Do I, though?"

I always like to think of myself as an engineer, and I talk about bridge building, you know, as an artist, and the gap that I'm trying to span is the gap between all of the different communities and cultures that I interact with.

[Cannupa] So, we're just rolling these cubes into spheres, and once they're spheres, you'll take one of these little skewer sticks and pierce the clay into a bead.

The grasslands where I'm from are dependent on buffalo, and so the 20,000 that are living wild today, I thought it would be a great gesture that we make a bead to represent each of them.

Even just rolling that clay in your palm, there is no two that will be the same, and the idea is us in relationship with one another.

♪pensive ethereal music♪ [Cannupa VO] So the bison bead project is part of this ongoing series called 'Counting Coup.'

And the intentions were basically just trying to rehumanize data, you know?

The first work in that series is called 'Every One,' and the number of beads represents missing and murdered Indigenous relatives.

♪♪ [bells jingling] Indian and American history aren't told in an honest format, they're told as myth.

It is the myth of the individual who had to raise themselves up out of nothing.

I like those shoulder pads with it.

All right, you got that pod?

[Ginger] Yeah, I got it.

I think it comes from, you know, a group of men who decided that they were no longer gonna be a part of England; you know, they were going to remove their self from their ancestral place.

And the violence that that displacement inflicts on everybody else around it?

You have to have this myth in place that justifies the brutality of individualism.

- Papa.

- [Cannupa] Yeah?

Do this.

[bells jingling] [Cannupa VO] But it's just a myth and it's just a story.

Okay, that's great.

When we do it again, spend a little more time going back-- like, featuring your back.

[sighs] Okay.

There is an entire ecosystem around successful artists.

They're getting support from their partners, from their parents, from their friends.

Thank you, Ginger!

♪curious ethereal music♪ I want to be artist/game designer... /YouTuber.

All I wanna do when I grow up is figure out... what I wanna do when I grow up.

I believe that when my children are my age, the definition and the exploration of what art is, hopefully, is so much broader.

It's like, "Can you do whatever you do beautifully in your life?

Can you make your life beautiful?"

Today, we celebrate individuals, we celebrate genius.

But... it's not sustainable.

♪tender synth music♪ [Ginger] Careful, buddy.

[Cannupa VO] We are dependent not just on each other, but our relationships to the environment and other species.

♪♪ The truth of our daily lived life is one of integration, is one of integrity.

That's how we survive the future.

[soil tumbling into wheelbarrow] [Linda VO] I came out of the womb knowing I wanted to be an artist, so that was always there.

And I started very young -- when I was around five or six.

You know, I'd have to tell a story about when I was, like, seven or eight.

I asked my father for a nickel to buy a popsicle, and his response was...

"No."

[laughing] I was like, "No?!"

So then I said, "How do I make a nickel?"

And I decided that the way to make a nickel was to get all the kids on the block... we could make a musical, not charge the parents to come, but make lemonade and sell the lemonade at nickel a cup.

And we were able to make enough nickels selling lemonade at our musicals so that we never had to ask for a nickel from a parent or anybody else for two summers.

[interviewer laughs] I have always believed in that.

And what did I have?

What did we have?

I didn't have any money.

I've never operated... Life is not dictated by how much money you have if you realize how many other resources that are much more valuable than that, like our imaginations and creativity -- much more valuable than that.

[laughing] And I learned that at the age of seven or eight.

♪chill funky music♪ I came to New York in '72, and I came to New York with two children and didn't know a soul, to go to grad school at City College.

So that's how I got here.

♪♪ ♪♪ I was working at The Studio Museum as Director of Education, and artists would come and get in conversations and stay all day, and it was wonderful.

But inevitably, at the end of every day, the conversation shifted to, "They won't let us.

They won't let us."

And the "they" was the art market, and they wouldn't let artists that were African American or other artists of color be exhibited.

So, my response to that was, you know, "[bleep] it.

Let's just do it ourselves."

♪upbeat funky music♪ And I heard about this gallery, and so I went down to the opening, and it was like Heaven.

[Linda VO] I mean, people were in the lobby of the elevators, they're down the stairwells, they're outside on the street trying to get into the gallery.

[Janet VO] It was just vibrant!

It was vibrant, it was alive, there were ideas, there were things I'd never seen before, there were things I had seen or could imagine making.

In the sense of ownership, in terms of doing this, even if you weren't showing there, you were creating a space that you could go to and see artwork of friends, of colleagues, and so it was a place of belonging.

of friends, of colleagues, and so it was a place of belonging.

♪cool jazzy music♪ And I was really interested in artists in LA; I was really interested in David Hammons and Senga Nengudi and Houston Conwill, and a host of people.

♪♪ At that time, there was a debate between Black artists who were working figuratively, and those who were working in an abstract or conceptual way.

And those many artists who were working figuratively believed you weren't a Black artist if you weren't working figuratively.

That came to a head at JAM, and it was David Hammons' first show.

Artists were like, "What is this mofo doing?"

And so everybody wanted to see it.

[Randy VO] David Hammons working with hair.

So much of the Black experience was about hair.

And so these experiences that you live, and how do you make those experiences into something that is visibly tangible?

And I think Linda was able to identify that very quickly, and say, "That's important."

♪♪ It started out for artists of color -- Black artists, mostly -- but then she started seeing work by white artists, women, and they were doing things that were just as experimental, just as nuts.

If JAM had only shown Black artists, we would've been replicating the racism and the segregation [chuckles] that the other institutions were doing.

Why would I do that?

So, in those early days, Wendy Ehlers showed work, and she made work with lint -- dryer lint.

I believe she had four or five kids, and she washed a lot of clothes.

♪upbeat funky music♪ So when we started JAM, I had enough money to ensure that we all had a buttered roll.

And people hung out at the gallery and worked; [chuckling] no one got paid.

So there was a buttered roll for anybody who was there.

[Maren VO] It was really hard.

It's hard to live in New York.

Linda struggled.

I don't know how many collectors she had, but I'm assuming there weren't a lot of collectors in the beginning for Black art.

[Linda VO] The primary objective was not selling the work; the primary objective was artists making the most amazing work they could make.

[staccato breaths] So the opportunities... the openness-- when I say "opportunities," just like, "What do you wanna do?

Do it.

What do you wanna do?

Do it," was just how we operated.

[woman] That looks very nice.

[man] Nice, it's nice.

♪energetic funky music♪ [Linda VO] You can say, "Well, how can you not worry about money?"

I never had money, and, you know, you can live without money.

There are other resources you can use.

And I discovered, when I started JAM, that one of the resources I could generate and use was debt.

♪quirky music♪ There were [laughing] always bills and past-due notices and "We're gonna take you to court."

Astor Wines & Liquor -- [scoffs] "Linda, you owe us how much?"

And I'd go, "I know, but we're having this opening, and we have to have some wine."

[chuckling] You know?

And he was like, "Ugh, all right, come down and get some."

When you're just that committed and passionate about something you believe in, other people believe.

♪airy ethereal music♪ [Ishmael VO] I think JAM acted as a catalyst.

I mean, the art, of course, was important, but it was also bringing an art community together -- bringing disparate people, disparate visions together.

And I think that's sort of her role in life kind of -- or her role in art -- is to create situations, and then, sort of like the mad scientist, watching what happens.

♪♪ [Maren VO] It was a wild and crazy, seat-of-your pants... You know, it was a conceptual idea that somebody made... visible.

♪♪ [sighs] Somewhere-- how about... somewhere in there?

[Maren VO] I made the decision to be an artist and I did it, and that's it.

I think this way.

It sure took me a long time to have a solo show or, you know, ongoing representation.

That began two shows ago.

♪♪ So, what, I was 70 already?

Okay, great.

Perfect.

[Maren VO] It was through Linda that I got my foot in the door.

And it's through her that my foot stays there.

[laughs] [Maren] I think it's looking nice.

[Linda] Yeah.

[Maren] So I'm happy about that.

[Linda] Yeah!

- Yeah, and-- - Yay!

And I don't think snow and rain or anything-- it's galvanized.

- It's beautiful!

- Yeah.

It's already beautiful.

[Maren VO] You felt her support, you know?

And you felt it was not just you against the world, it was you and her against the world.

[Linda] This is really... how I kind of imagined it.

- [Maren] Oh, good!

- [Linda] Yeah.

No, this is fantastic!

- [Maren] Okay, great!

- Great!

And I'm glad you're warm... - almost.

- Uh, well... - [Linda laughs] -Yeah.

Tighten up, tighten up!

Art is... evidence of life.

The art is the life that you live.

I mean, you could be an artist and never make work.

♪♪ [Linda VO] It never really was about objects, it never was about commerce, it was about creativity, and frankly, JAM was an artwork for me.

- [Linda] Hi.

- [woman] How are you?

[Linda] I'm good!

I was trying to decide if I was gonna squat.

[Linda VO] First of all, I believe all humans are artists.

[Linda] But I am not a great squatter, so I think I might keep shoveling.

[laughs] We are the only species -- humans [laughs] -- are the only species that we know of to date that have the ability to imagine and transform what we imagine in our heads -- the visions we see -- into something tangible that others can experience.

[Maren VO] She has this project EATS now, which is feeding people.

So it's an offshoot of the whole gallery idea.

♪tender music♪ Well, my mission here is to learn how to grow in feeding my elders, my age, my peers, and our children more healthier foods.

This is all been here since May.

[woman] Oh, wow.

[Linda VO] We are currently operating six farms.

We should all be able to grow our own food where we live.

Even if we live on concrete, we should be able to pull that off.

So anyway, that's my art now, is Project EATS and feeding people.

♪soft uplifting music♪ When I was approached about doing a MoMA show, I was reticent and, you know, like, "Mm, I don't-- that's not where I'm at."

But as I thought about JAM and MoMA being four blocks away from one another and MoMA just totally ignoring Just Above Midtown, I got this notion in my head about, "Is it even possible for JAM to be JAM at MoMA?"

And I like a challenge.

I love a challenge.

♪♪ [Randy VO] To have a belief in yourself and a belief in your artists, that is so affirming.

I often think of someone sitting in a rocket ship on their way to the moon, and being so confident [laughs] that they're gonna get you there and back.

You know, and I think Just Above Midtown had that type of confidence -- that "We will get you there and back."

♪♪ [Linda VO] That JAM could be JAM at MoMA?

Shoo... Yeah, that was-- like I said, I could really, really, really look up and see the elders sitting in the rafters and say, "Y'all did it.

Y'all did it.

We are here.

We're in the infrastructure of this mofo now."

And I like that, because we should be, we should have been, and... and we are.

♪ethereal ambient music♪ [man VO] 'Art in the 21st Century' is available on Amazon Prime Video.

This program was made possible by: the National Endowment for the Arts... Lambent Foundation... the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation... the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts... the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation... Toby Devan Lewis... Robert Lehman Foundation... Nion McEvoy and Leslie Berriman... and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

Artist Miranda July Performs At a Gas Station

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S11 Ep3 | 1m 30s | Artist Miranda July performs at a gas station in Los Angeles, California. (1m 30s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S11 Ep3 | 30s | Artists look to friends, family and strangers to find emotional connection and community. (30s)

"Future Ancestral Technologies"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S11 Ep3 | 1m 17s | Artist Cannupa Hanska Luger talks about his series, “Future Ancestral Technologies.” (1m 17s)

The Origin Story of the Art Gallery "Just Above Midtown"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S11 Ep3 | 1m 17s | Artist Linda Goode Bryant shares the origin story of the art gallery, Just Above Midtown. (1m 17s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Arts and Music

The Best of the Joy of Painting with Bob Ross

A pop icon, Bob Ross offers soothing words of wisdom as he paints captivating landscapes.

Support for PBS provided by: