Fossil Country

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Fossil hunters seek their fortunes in remote western landscapes.

Hardscrabble fossil hunters in Wyoming make astounding discoveries that change what we know about the earth’s history. The mining town of Kemmerer, in the Green River Formation, is ground zero for the best fossil collecting in the world. Geology, history, and entrepreneurship all come to life through human stories of fossil hunters seeking a rare discovery — and a big payday.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Fossil Country is a local public television program presented by Wyoming PBS

Fossil Country

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Hardscrabble fossil hunters in Wyoming make astounding discoveries that change what we know about the earth’s history. The mining town of Kemmerer, in the Green River Formation, is ground zero for the best fossil collecting in the world. Geology, history, and entrepreneurship all come to life through human stories of fossil hunters seeking a rare discovery — and a big payday.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Fossil Country

Fossil Country is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

[bird chirping] [Narrator] Fossils are found everywhere on Earth.

[Narrator] Fossils are found everywhere on Earth.

In most places, all that's left behind are traces of bones or shells.

all that's left behind are traces of bones or shells.

But in the high mountain deserts of southwestern Wyoming lies some of the most perfectly preserved remains of ancient life.

[orchestral music] Frozen moments in time.

Frozen moments in time.

Fossils tell stories of life that refuse to disappear.

of life that refuse to disappear.

Traces of their existence lingers on long after the world has changed around them.

This is the story of fossil hunters who search for treasure like the gold miners of the Old West.

like the gold miners of the Old West.

They endure extreme weather and treacherous slopes in the hopes of a major discovery and a big payday.

- Oh, my God!

- Cha-ching.

- Cha-ching.

[Narrator] There is a scientific side to the story of fossils, but there is also a human inside.

but there is also a human inside.

[clapperboards clapping] [orchestral music] [orchestral music] - I've studied fossils all around the world for my entire career.

And I still maintain that Wyoming is the best place on planet Earth to look at the fossil record of our planet.

of our planet.

I encountered people that for many years and sometimes, generations, have been commercially collecting fossil fish and selling them around the world.

- There's millions of years of fossils in there, but trying to find a good one and splitting the right layers is what we do.

is what we do.

- I like fossils.

I chose fossils.

It's not a lucrative career.

It's not a lucrative career.

It's hard, but it's rewarding.

- Another one in the bag.

- The people that do this for a living, the commercial enterprise, they understand what they're saying, they know the of layers, all know these rocks better than I do.

all know these rocks better than I do.

- They live in campers, they're nomadic, gritty people, good people, I think.

good people, I think.

- But there is a controversy about the sale of fossils privately.

They should be the public trust.

They shouldn't be subject to general ownership.

- Some people say that we don't know exactly what we're doing, we don't have any formal education, but we actually do care about the scientific value that goes into the specimen that we pull on the ground.

We wanna know this information.

This is our love, this is our passion.

- All the stuff that's in that book came from people like me digging it out of the ground.

came from people like me digging it out of the ground.

And America's just about the last country where fossils are still a free enterprise.

where fossils are still a free enterprise.

- The United States is one of the few jurisdictions where it's legal to collect and export fossils.

- They've been trying to put a stop to all that, and we, as a group, have been fighting back.

- But literally, millions have been excavated.

As a result of those millions being excavated, the much less common things are found.

- I tell people I wish I'd have got in the business of selling feathers instead of rocks.

My knees are shot.

I worry about the dust.

The elements are brutal.

I can't quit.

I don't know what else to do really.

I don't know what else to do really.

I wouldn't know how.

[laughs] [laughs] - Major funding for this program was provided by a Memorial gift honoring Betty Buckingham Baril, PhD, and her passion for the natural world and science education.

and science education.

The Wyoming Communities Council.

Helping Wyoming take a closer look at life through the humanities.

The Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, because culture matters.

A program of the Wyoming Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources.

Wyoming Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources.

A generous gift from MAS Revocable Trust.

And the Wyoming Public Television Endowment.

And the Wyoming Public Television Endowment.

[dramatic music] - I ended up with the perfect summer job for someone like me.

- I ended up with the perfect summer job for someone like me.

I'm the paleontology intern here for the summer at Fossil Butte National Monument.

at Fossil Butte National Monument.

You have one active quarry here on the monument.

It's our research quarry.

It's not a very big quarry.

My days up here at the research quarry are probably my favorite, personally, cuz I get to be outside all day.

I get to hike up here.

It's a beautiful view.

And then I get to start finding these fish that no one has ever seen.

And I get to collect the data and the data is publicly available.

So it's really, really exciting to be able to be just a part of the whole process.

be able to be just a part of the whole process.

- We started collecting here in 1997.

- We started collecting here in 1997.

We've been working this down since 1997.

That's a long time.

It's the last couple years we've had our staff work in the quarry, and then they are working two days a week, all day long even if visitors are present to try to move this process along.

- People can just walk up and take the trail up to come see what I'm doing up here.

Luckily it's like a perfect mix of getting work done and talking to people.

- Fossil Butte National Monument is a small monument -- 8,198 acres in Southwest Wyoming.

8,198 acres in Southwest Wyoming.

We are established for the geology and paleontology of this area.

and paleontology of this area.

What's behind me right here is what we're supposed to do is get them out there for the public.

is get them out there for the public.

It's a national park service land.

So it's public land.

[soft dramatic music] - Of course, out of this quarry, we're only getting maybe 500 fossils a year and that's shooting pretty high.

And for a lot of the rare fossils, so the mammals, for example, if we had only been mining here, there's no way we would've ever found something like that.

So the commercial quarry is... since they are doing such a huge quantity of fossils every year, they really find a lot of the more rare discoveries.

Which helps us get every little corner of the ecosystem and build a better picture.

[dramatic music] ♪ [hammers tapping] - We're able to go through a lot of rock.

We are lucky here because we have a good relationship with the national monument.

With Arvid, who's phenomenal to work with.

With Arvid, who's phenomenal to work with.

[engine puttering] I came here for a summer time job in college.

I came here for a summer time job in college.

Got introduced to digging fish out here and enjoyed it.

And then I became the museum curator and served as the paleontologist for Fossil Butte National Monument.

for Fossil Butte National Monument.

I live in Kemmerer.

I like small town, I grew up in a small town.

Kemmerer been good to us as we raised our kids here, my wife and I.

It's a nice community.

[piano music] [Narrator] Fifteen miles from Fossil Butte National Monument is the town of Kemmerer.

is the town of Kemmerer.

- Kemmerer's an interesting town.

It's famous for a few things.

It was the mother store for J.C. Penney's.

Kemmerer was also, and is still famous for coal.

I mean they had these enormous coal mines.

- Kemmerer is a surname of a German gentleman who funded the coal mining around this area.

who funded the coal mining around this area.

- When I came here, the city council would kinda laugh at me sometimes cause I would say Kemmer-er.

- K-E-M-M-E-R-E-R, so Kemmer-er.

We say Kemmer, just drop the last E-R. - Kemmerer was a vibrant town.

I mean we had huge parades and people in the streets.

It was an the amazingly vibrant merchant class.

And growing up with those people was just a wonderful experience.

was just a wonderful experience.

- We have some challenges and it's really actually... we're at a crossroads in many ways.

Rocky Mountain Power has announced that they will be closing our power plants.

that they will be closing our power plants.

- The businesses have disappeared.

- The businesses have disappeared.

You have a hard time maintaining restaurants.

You have a hard time maintaining restaurants.

- The town of Kemmerer was doing fine, cuz there was 300-400 coal miners and lots of work going on.

But they've gotta find something different.

A lot of the locals, fossils goes right over their head and they don't realize what they got in their backyard.

and they don't realize what they got in their backyard.

- R. Lee Craig, 'Peg Leg Craig' was the father of commercial fossils.

was the father of commercial fossils.

Lost his leg in a mining accident out here in the coal mines in the early years.

'Peg Leg Craig'.

Kinda was limited to what he could do from that point on to make a living.

He would take his wheelbarrow and his very primitive tools to dig these fossils and then prep them with a little pen knife.

and then prep them with a little pen knife.

- Well the railroad came through and now you didn't have to haul fossils outta here on a horse or a pack mule or a wagon.

There's a railroad.

- And he would meet people at the train station and sell fossil fishes to people running either east or west and make a living, you know, up until he passed away in 1938, I think is when he finally died.

- He was joined by the Haddenham family in the 1920s who then went up into the 1950s collecting the fossils.

And then the Ulrichs picked up in the late 50s and carried on.

And then we have an explosion of quarry activity in the late 70s and into the 80s.

With now, there's over 20 households making sole-source income off these fossils here.

making sole-source income off these fossils here.

- My first year out here, of course I met Carl Ulrich and he brought commercial paleontology out of just the Ma & Pa shop type of thing, in the 50 and 60 and 70s.

Ulrich was the premier fossil fish person in the world.

Ulrich was the premier fossil fish person in the world.

- My father was Carl Julius Ulrich and he was born in 1925.

My mother was born in 1926.

My mother was born in 1926.

And mother was a businesswoman.

So they made a heck of a team.

By 1960, that was the year that President Eisenhower chose one of the very large beautiful Diplomystus.

The gift to Emperor Naruhito, the Emperor of Japan.

There was a family discussion at the kitchen table one evening about... my mother brought up the question, she said, "You know, Carl, do you really want to do this with what happened to your brothers?"

My dad lost two brothers.

My dad lost two brothers.

They were both killed -- by one, Japanese Navy sinking the USS Houston.

And then Leroy was killed by the Japanese.

He was bayoneted at the camp called Cabanatuan.

In Kemmerer, Wyoming, we sent a lot of young men there and they were prisoners of war.

They were terribly abused.

Dad's response was very quick and eloquent.

He said, "I don't know if the Emperor started the war, but I do know that he ended the war."

but I do know that he ended the war."

Dad built a huge crate.

Remember it going off and getting on the railroad and headed to the White House.

and headed to the White House.

The son of the Emperor then went to the White House and received that gift and took it back to Japan.

and took it back to Japan.

- And so from the President of the United States gifting a Diplomystus to the Emperor of Japan, that they had bought from Carl Ulrich, it was just really wonderful to watch that happen.

And now we're the old timers.

I remember when we were the youngsters.

When I was doing it early on, there were only a few of us, families that continued generation after generation of that family working in that.

- The ones that have been doing this the longest, I'd have to say is the Tynsky family.

Three generations of Tynsky's were digging.

'Picking fish' is what they called it.

[laughs] So they were, you know they started probably in the 60s.

they started probably in the 60s.

- My grandfather's name was Sylvester Tynsky.

Everybody called him 'Swides.'

My dad and grandpa had a rock shop.

I would go out with him when I was just the little boy and I would help him hunt rocks and look for wood and stuff.

Basically, we were rock hounds or fossil people.

My job had just been digging and collecting and preparing fossil fish.

That's what I've done for 40-some years.

That's what I've done for 40-some years.

My dad got a quarry up here with the rancher, made a deal with him and I started working with my dad.

And then when my dad passed away, I pretty much took it over.

I pretty much took it over.

- My wife and I moved here, bought my dad's business to help him, cause he was going through cancer.

[gentle music] - It has changed a lot.

When we first started, there was just a few of us doing it.

And now there's quite a few people involved in it.

[guitar music] [guitar music] - Oh yeah, they're pretty competitive, yep.

We get along.

We don't get along or really get together a lot.

We just say, "Hi," and wave when we see each other.

We try to get along, you know and it works out good for most of the time.

and it works out good for most of the time.

- Dean is the new kid on the block.

And there's an up and coming new generation.

Gotta happen.

- Jim Tynsky is my father-in-law and our company name is In Stone Fossils.

I started my career with oil and gas and then I don't wanna do what I'm doing anymore.

I want to dig fossils until basically the day I die.

- Wow.

- There we go.

Check that out.

[wind blowing] [dramatic music] ♪ [Narrator] Winter falls across Wyoming.

[Narrator] Winter falls across Wyoming.

The ground is now too frozen to dig.

♪ This is the season for the fossil hunters to prepare their finds.

♪ - Come on girls.

[chickens and ducks cluck] ♪ - Good, they will pick on that all day long.

[chickens cluck] [chickens cluck] [dramatic music] - My name is Rick Hebdon.

♪ My dad had to work hard for everything he did.

No college.

He didn't get even outta high school.

I think of with my part especially, it was kind of a destiny.

My father owned sheep, big sheep rancher.

My father owned sheep, big sheep rancher.

We used to have to trail the sheep from the Kemmerer, the spring range, out to the desert.

out to the desert.

And we had, it was about 2,500 head at that point.

at that point.

The pound of wool was, you know, I think a dollar a pound way back then which was equivalent to $10 when I was in the business, you know.

So it was, it was a valuable commodity.

So it was, it was a valuable commodity.

And the late fall, November, we would trail out to the desert and that was down by Little America, Flaming Gorge, all over that country.

We could go anywhere we wanted to.

We could go anywhere we wanted to.

We used to go to the springs, Orfield Springs, to get water for the sheep camps.

to get water for the sheep camps.

I was dumping water into the cans and I looked down and there was a fish.

and I looked down and there was a fish.

This is probably one of the first ones we found.

This is probably one of the first ones we found.

And I could see that I could make a living at it.

And I could see that I could make a living at it.

[Narrator] Commercial quarriers, like Rick Hebdon, make a living, in part, by selling important fossils they found to prestigious museums.

[dramatic music] - The Field Museum in Chicago, they support commercial collecting.

Their curator, he saw a win-win situation.

He comes here and buys the stuff from us, takes it back to the museum and they sit and describe it for years.

Literally.

I've sold him a whole collection of birds.

And I think there was five brand new birds in that collection.

And they're still working on that pile of birds.

And consequently, they've got the greatest collection of Green River fossils in the world.

of Green River fossils in the world.

- When you have things as delicate as complete bird skeletons with all the feathers still attached.

Or complete bat skeletons or flowers or things like that, that are perfectly preserved.

You know, these things just sunk and were buried relatively quickly or at least before they had a chance to decompose or be torn apart by scavengers.

or be torn apart by scavengers.

Fossil Lake is really a precious locality because for one thing, it's the best picture we have of how North America was recovering after the great extinction at the end of the Cretaceous.

after the great extinction at the end of the Cretaceous.

- Southwest Wyoming is the Green River Basin which is a huge, broad expanse.

These were landscapes that when they formed were lakes in a subtropical or tropical climate.

[birds chirping] [birds chirping] But today, it's a wind blown cold desert.

[wing blowing] The world was a very different place than it is today.

For one thing, there was no polar ice caps.

So there's natural slow geologic processes that both increase greenhouse gases and cause the earth to warm and also remove those greenhouse gases and cause the earth to cool.

So we see in the past times when there was ice covering the entire planet and times there were no ice at all.

And those are purely natural processes, which meant that it was a warm world and Wyoming was warm and wet.

And in the Kemmerer lake beds, we find not only fish but we find mammals and birds and reptiles and amphibians and plants.

and amphibians and plants.

It's sort of like Costa Rica.

It's sort of like Costa Rica.

when mountain ranges pushed up and the area between the mountain ranges formed basins.

They formed in southwestern Wyoming, in northwestern Colorado, and then northeastern Utah.

and then northeastern Utah.

Basically an organism has to die and then get buried in a place where the land is sinking and you get buried under great depths of sediment which eventually compacts into rock, and eventually in some places the sediment gets pushed back to the service or to roads and the fossil effectively becomes unburied.

So you have die, get buried, in order to be found, you have to be unburied.

Basically that's your recipe.

Quick death and quick burial is a good recipe to make a fossil.

is a good recipe to make a fossil.

We're in the National Museum of Natural History where we've got over 45 million fossils.

So it's the largest collection of fossils in the world.

So it's the largest collection of fossils in the world.

Part of my job description is to go after these kinds of really rare, incredibly gorgeous things and make sure they're preserved forever.

and make sure they're preserved forever.

For a paleontologist, that state is paradise.

[hammer tapping] [hammer tapping] [hammer tapping] [hammer tapping] - Oh, my God.

- Wahoo!

- Wahoo!

[Narrator] Each quarry offers something unique.

[upbeat music] - So we use them, incorporate them with back splashes in homes, fossil murals of artwork for homes.

fossil murals of artwork for homes.

[Narrator] Some quarries focus on fossil tourism.

- This right here, are a bunch of tiny scales from fish from... from fish from... - This used to be, what was called, the Outlaw Quarry.

It was not a place that you would want to send your family.

[laughs] To get this going, we really wanted to have a place that was friendly for people; ladies, kids, whoever wanted to show up, and that enjoys fossils.

[saw blade whirs] [tapping] - Oh!

- Oh!

- Nobody home.

What's that little thing?

What's that little thing?

- I used to work here at the quarry.

I managed the public dig for the summer of 2012.

I definitely met a lot of tourists.

They don't know what to expect.

There were a lot of people that were like, I don't know, they had no preconceived notions of what a quarry would look like, for sure.

would look like, for sure.

The questions they would say, like people would be like, 'fish?'

and they look around and they're like, "What's a fish doing out, you know, up here?"

[tapping] [tapping] - Me too.

[upbeat music] - We'd let people come and dig, charge 'em a fee and they get to keep the fossils.

They can't get enough.

[upbeat music] ♪ [rock crunching] [dramatic music] [Narrator] Opening up a new section of the quarry requires heavy equipment.

Rick Hebden drives his backhoe across the top of the mountain, scraping away the dirt to get down to the rock.

The road he is on didn't exist two hours ago.

♪ - You're looking down at a cliff and you have to like start pushing and let it drop over the edge.

And it gets a little hairy, you know.

Those rocks are trickling way down there.

It's kind of scary from that seat.

[laughs] Hanging onto the seat, pushing that stuff right over the edge.

And it's a long drop down there.

[dramatic music] ♪ You gotta push right to the edge, ya know.

♪ ♪ It burns a hundred gallons of fuel a day and it hurts the pocketbook, you know.

So sometimes I have to like let the money build up before I can spend it.

[laughs] [laughs] - The best analogy is you take a cake and you slice a cake in half, you can see the layers in the cake.

You know that there's layers there and the layers themselves are horizontal features, but by slicing it, you see them in cross section.

And one of these little layer is called the 18-inch layer cuz it's 18 inches thick or maybe 20 inches thick, is a layer that is got a very dense kind of marrow and it's one where, for whatever reason, the fossils are better preserved there than they are elsewhere.

It's sort of the sweet spot in Fossil Lake where the very best and most beautiful fossils, the fossils there tend to have a nice dark brown, almost black color to them.

There's just no debating that thing is an ancient fossil.

[upbeat music] - You guys ready to go?

[all chatter] [all chatter] - I say we wager.

It's 10 bucks in the pot for everybody.

And whoever catches the biggest fish.

- Biggest complete.

- Biggest like, end to end fish wins the kitty.

What do you guys say?

[Man] All right, sounds like a deal.

[Man] Sold.

[Man] We'll see how it goes.

- So it was my grandpa's idea.

He organized the whole thing.

He just said that we would be coming out here and there would be fossils out here that it was a famous area for finding fish.

that it was a famous area for finding fish.

- I was always picking up rocks.

Finding arrowheads before it was illegal.

Finding arrowheads before it was illegal.

Wish I knew more kind of thing.

- It's the stuff that I dig.

Okay?

I'm giving you the stuff that I dig.

We have some shims here, some hammers.

So selectively grab what you need.

So selectively grab what you need.

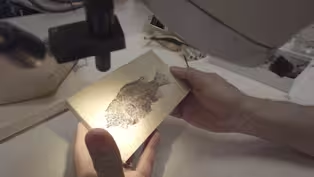

[Narrator] The tools have changed very little in a few hundred years.

in a few hundred years.

Wedges help peel the rocks apart.

And reveal the ancient life hidden in the stone.

And reveal the ancient life hidden in the stone.

- Just lift it up.

- Just lift it up.

I didn't steal your thunder there.

[Man] Let's do it, let's reveal what's in here.

[Man] Let's do it, let's reveal what's in here.

- And you have a bunch of Knightia.

[Man] Oh, look at that.

- So we take a pick and we split each section of rock about a half, and then depending on the layer, if you get lucky or not, there's a couple fish fossils inside of each layer of rock.

- Sweet.

[Man] Yeah.

- Every layer, there's just different things that can be on the rocks, and... [scraping] - Okay.

- Okay.

Take your shovels out.

Take your shovels out.

And we'll lift it.

And we'll lift it.

Three, two, one.

Three, two, one.

There we go.

And look at those fish right there.

[Man] Oh my word!

[man laughs] - Oh my God, look at that fish!

- Oh my God, look at that fish!

[Man] They're everywhere.

[Man] They're everywhere.

- That is freaking... That's a good one too!

Like, seriously!

That's awesome.

That's a beautiful plate.

That's a beautiful plate.

Yeah!

Yeah!

[Man] Fossils, it's like a mystery.

You never know what's gonna open up when you crack that rock open.

[upbeat music] [Narrator] Some quarriers would prefer to work in darkness.

in darkness.

[generator starts and revs] - We do it at night because one, we can control the lighting.

And two, it beats the heat in the day.

[calm music] That quarry out there, nothing shows up in the middle of the day.

You can't see anything on it.

You can't see anything on it.

Turn on the generator, got the lights all parked the way we want them, and man, stuff just sticks out everywhere.

You gotta see it to believe it, 'cause from what was absolutely nothing in the middle of the day, you come back at night, it's like wow!

Pad's got a hundred fish on it.

Copra lights and everything that was there shows up.

- Here's a good one.

- Here's a good one.

[hammers tapping] - Can you see this?

This little line that's kind of a divot here?

[Man] Yeah.

[Man] Yeah.

- This will be a plant.

So plants leave impressions instead of bumps.

So when you're looking for big plants or anything, you're looking for this sort of thing.

Sometimes you can see them branching out or find palms that way.

or find palms that way.

- We use lights at night to cast an accent shadow across, so that's how we discovered fossils.

Really fragile, but we can save that one.

That is pretty.

First frisky of the night, look at that frisky.

[Man] That's beautiful.

[Dean] That's as pretty as they come.

[Rick] I like it out there.

We really enjoy to be there.

It's hard but it's real rewarding.

It's hard but it's real rewarding.

- Oh wow.

Wow.

- Oh wow.

Wow.

- So this exploded guy.

That's an awesome fish.

That's beautiful.

Cha-ching.

- Cha-ching.

[laughs] That's a myolysis.

[Man] Isn't that pretty?

- It shows up nice.

- Wholesale, 'cause that's mostly what I do.

Wholesale, that's like, $1,000.

Retail, you know, is double that.

Besides going ouch.

[grunts and groans] But you're like, "Whoa, we really kicked ass.

We got a lot of fish tonight."

You know?

[man laughs] It's like a gratification.

- When I see those lights on in those quarries, I'm like, "Man, they found something good.

I want to know what they found.

I want to know what they found.

I want to see something crazy."

[dramatic music] [Narrator] When diggers do find something rare, they have to involve the landowner.

they have to involve the landowner.

And split the profits.

And split the profits.

- I'm Roland Lewis and I'm 85 years old.

- I'm Roland Lewis and I'm 85 years old.

My grandfather, Richard Henry Lewis, first came into the area here in 1870.

He ranched it, he raised horses.

He ranched it, he raised horses.

He ran a bar in the town of Fossil.

[laughs] The quarries are on lease.

And the quarry lease is based on a percentage of whether we sell prepared fossils or unprepared fossils.

or unprepared fossils.

- There are a number of quarries that are located on the Lewis Ranch.

And it's mainly these little outcroppings on the shelves that surround the area.

So, to date, there's probably five or six quarries that are on the Lewis Ranch -- separate quarries.

[calm music] - Before the commercial private quarries, there wasn't a lot of species being identified.

species being identified.

Since we've opened up that exploration with private, we've found so many more species and types of species and such.

and types of species and such.

[Narrator] These amazing fossil discoveries have drawn academics and students to Kemmerer, where they do their field studies.

They're developing a new understanding of the land through scientific methods.

Professors use the quarries as a classroom, teaching their students about geology and paleontology.

- How many quarries are you in?

- I've got three.

- Okay.

- I've got Warfield Springs, I've got this one, which is private ground, and then I've got the one on the state section.

Which we're going to this evening.

They call these the sandwich bits because of these distinct ash layers.

But the fishes actually start, can you see the dark line up at the top?

can you see the dark line up at the top?

Just a half inch above that.

I take a measurement, every time we find anything significant.

anything significant.

- I think Rick is an artist.

- Like I said, we'll cut them so that... - Like I said, we'll cut them so that... See how I've made him swimming up at a faster pace, right?

If you put him straight across, he's just kind of floating along blowing bubbles, he's not doing anything.

You put him swimming downhill, he's seen something, he's on a mission, or he's trying to get away.

- Not only is there science behind it, but there also really is creativity and art, and his expertise.

- I had no idea what a private fossil quarry would look like, honestly.

I don't think I would've guessed that it was something like this where you have folks from the National Monument coming out, in addition to the academics.

in addition to the academics.

And academics from all over the country coming to see stuff.

I wouldn't have guessed that, certainly.

- I have got half a dozen really cool, awesome mammals out of here.

And at least two or three of them is brand new species.

And at least two or three of them is brand new species.

So yeah, I've gotten eight holotypes out of here.

Five paratypes.

- A holotypes is the first ever described of a species.

So they're really important.

- Yeah.

- Yeah.

But it's gotta go to a museum.

And then part of the money's gotta go to look for more stuff.

All right.

I got the backhoe fixed.

I got the backhoe fixed.

All right, you guys wanna dig?

[All] Yeah.

- Let's go over here, this side.

- Let's go over here, this side.

And you can split some fish.

And you can split some fish.

- It's a great environment to bring students.

I bring my University of Chicago class out there every summer.

- It's gorgeous.

- Wow.

- Awesome.

- Wow.

- Awesome.

- That's where I do all of my field work.

And the curators at the field museum and most major museums are research positions.

and most major museums are research positions.

One of the largest collections we acquired was from one of the quarriers, Rick Hebdon, and it included an amazing amount of really unique specimens.

Including the earliest known mammal with a prehensile tail.

That is a tail where it's effectively a fifth limb.

It could swing through the trees on this.

And it's absolutely complete.

And for early Eocene mammals, that's amazing.

And for early Eocene mammals, that's amazing.

- And that little mammal with the prehensile tail, that's a totally undescribed little beast, and it came from people like me digging it out of the ground.

digging it out of the ground.

[Dr. Grande] We want to see those collections preserved in perpetuity in an institution, like The Field Museum.

like The Field Museum.

- There is a lot out there.

You figure there's millions of years of fossils in there.

But trying to find a good one and splitting the right layers is what all we do.

and splitting the right layers is what all we do.

This is where I spend most of my time digging, down here.

This is where I spend most of my time digging, down here.

You can see these.

You can see these.

And you never know what you're gonna find when you're digging this stuff.

when you're digging this stuff.

- Fossil Lake is very well-known for the fossil fishes.

That's what we're known for, world wide.

That's what we're known for, world wide.

Millions have been excavated.

Literally, millions have been excavated.

As a result of those millions being excavated, the much less common things are found.

the much less common things are found.

[Narrator] This is Jim Tynsky with his son and grandson at their fossil quarry on the Lewis Ranch.

at their fossil quarry on the Lewis Ranch.

Less than a few hundred yards from here, Jim Tynsky was splitting rocks one morning in September 2003.

Jim was about to make one of the greatest fossil discoveries to date in South Western Wyoming.

fossil discoveries to date in South Western Wyoming.

Where'd you find the horse?

- The horse was found up higher in the up above layers.

in the up above layers.

It was late in the year, and it was Scott Banta was working with me.

and it was Scott Banta was working with me.

And the first rock I split, I seen a leg sticking out.

And we got all excited and we split the rest of it, and lifted it up, and we could see the horse laying there.

and lifted it up, and we could see the horse laying there.

Most fossils were in natural faults or cracks.

And when you go to lift them, they break, and then you have to put them together.

So this was unusual that the head was like, a couple of inches from one edge of a crack, and the foot was like, a couple inches from the other side.

If it would have been laid out any different, a lot of it would have been missing.

So we were very lucky.

So we were very lucky.

Most amazing day I've ever had.

Finding a three toed horse then was the ultimate.

[Interviewer] What goes through your mind when you find something like that?

- "Oh my gosh."

[laughs] [laughs] - I got a phone call from my dad.

I was so excited, it even brought tears to my eyes.

- He called me and asked me, "Hey, I've got something really amazing in the ground."

"Hey, I've got something really amazing in the ground."

And he didn't tell me what he originally had found.

He said "I got something really great in the ground."

He said "I got something really great in the ground."

- We all piled in the Green River Stone Company truck, and drove over to the back quarry, as we call it.

We get out of the car and walk over, and there it is, a perfectly articulated horse, just laying in the ground.

And couldn't really believe what we were looking at.

It was kind of a mystical feeling.

It was kind of a mystical feeling.

- I received a phone call from my wife.

And she said, "Hey, Alex, my dad found a horse."

I'm like, "No, no, no, that ain't real.

"That's the unicorn, that's an urban legend.

That ain't gonna happen."

- That's probably the holy grail, definitely, of mammals.

[Alex] How does a horse get out in the middle of a lake?

Well, this did.

Well, this did.

It's like hitting the lottery.

It's like hitting the lottery.

- I was sitting in my house in the living room.

For several years it was in here, I didn't know where else to keep it, you know.

I didn't know where else to keep it, you know.

[calm music] - As soon as you find a specimen like that, you'll start getting phone calls.

And people wanting to acquire it.

And you kinda gotta sit back and think about "Okay, how important is this specimen?

and think about "Okay, how important is this specimen?

Let's contact the museums first.

Let's see their reactions."

Let's see their reactions."

- I wanted to see it go out to the Monument, which you know, I was hoping too.

But they just never had the funds.

- Ah, we could've had it here.

And he was excited for that.

Jim wanted it to come here so he could come here, he could bring his grandkids here and say "I found that."

he could bring his grandkids here and say "I found that."

- There's a period of time that passes where, you know, people may approach you trying to buy something, and there's nothing wrong with listening to what they have to say.

Also, with the landowner as well.

Then you make a decision moving forward on what needs to be done.

- For finding something like that, that's like finding a big golden nugget.

You know, you've worked your butt off your whole entire life to find something so magnificent.

That's basically like, a lot of people say is like your retirement.

is like your retirement.

[Narrator] Quarriers and landowners have been selling fossils to private buyers for centuries.

Some paleontologists express concern that the institutions are being priced out of the market, with rare fossils lost to private collections.

with rare fossils lost to private collections.

- A lot of academics are really against commercial collecting.

And they make it their goal to try and make it tough for anybody else but them to deal with fossils.

to deal with fossils.

- The problem with commercial collection is not that commercial collectors are all rapacious and evil.

Or that they're, you know, taking all the fossils forever.

The problem is, specifically, that there is a limited supply.

Vertebrate fossils are very rare.

If the fossil is not in a museum, then it's not necessarily accessible.

And that dead ends the science.

And that's not how science is supposed to work.

And that's not how science is supposed to work.

If the fossil is in a museum, then it's available for study.

And as close to perpetuity as we can guarantee.

They should be the public trust.

They shouldn't be subject to general ownership.

They shouldn't be subject to general ownership.

[Narrator] The concern about private ownership is illustrated by a recent case.

In Montana, two dinosaurs were discovered that appear to have died while locked in battle.

An extraordinary find.

An extraordinary find.

Thomas Lindgren was asked to help find a buyer for the dinosaurs.

After several museums declined, the dueling dinosaurs were taken to an auction house.

the dueling dinosaurs were taken to an auction house.

- My father branched out and started working with Bonhams & Butterfields, an auction house based out of Los Angeles, on the high end commercial market.

- I took the dueling dinosaurs to Bonhams and offered the most important and most significant dinosaur fossil ever found in North America.

And the scientists shot me down.

And the scientists shot me down.

- What we're trying to do is make the issue public with the auction houses and make as big a stinky as we can, because fossils should be for everybody.

- The aspect that these were commercially collected has created a little bit of a controversy in the scientific community.

There are those scientists that believe unless they have had the opportunity to actually work on them themselves, they have no value.

One of the comments was made, "All the fossils should be seized from that auction using imminent domain, because they should belong to science."

because they should belong to science."

What?

- In the United States, at this time, there is no restrictions on private land fossils.

They can be collected and held privately, or sold, or however, and they don't have to tell anybody.

- The United States is one of the few jurisdictions where it's legal to collect and export fossils.

- Most other countries, what's under the surface belongs to the government.

In America, it's private.

In America, it's private.

If you own this block of ground, and the mineral rights, it's all yours.

So if you wanna drill for oil, it's yours.

So if you wanna drill for oil, it's yours.

- Many museums can't afford very many specimens.

And if they're lucky enough, they might get a donor.

But the donors don't necessarily have the same priorities for specimen acquisition that the curators do.

And furthermore, the big auctioning market for big dinosaurs is driving black market fossil sales.

We're not trying to ban sale of fossils altogether.

But if it's scientifically significant, it should be in a museum.

[Narrator] In the end, the dueling dinosaurs did not sell at auction, due to the outcry from scientists and the Society of Vertebrate Paleontologists.

However, a museum in North Carolina purchased the fossils.

A happy ending.

Ever since then, as soon as a rare fossil is discovered, there is tension around whether it will be sold to a private buyer, or end up at an institution.

or end up at an institution.

- Without the commercial investment, the dueling dinos would have never been found.

They were found, they were collected by a private commercial company that did it in a manner of documentation and expertise, that very few museums even have.

- They're trying to rewrite all the regulations.

So it is a constant battle to keep up with them and not let them stop you, you know, from what we do.

- A lot of people think people are getting rich over these things.

And what they don't understand is the cost of doing business is actually quite large.

is the cost of doing business is actually quite large.

- There's this balance there.

The quarriers want to get them to museums.

But they also need to pay their bills.

And so this is their livelihood.

And so this is their livelihood.

- I call people wheelchair paleontologists, not to be disrespectful, but they don't get out of their damn chair in their office, you know, and we're out here doing stuff, finding stuff.

Making stuff happen, so.

Yeah.

The digging, collecting of fossils would slow down to a snail's pace if it wasn't for commercial people.

if it wasn't for commercial people.

- There's plenty of fossils for little kids and amateur collectors and commercial collectors, and professional academic collectors.

There's plenty of stuff to go around.

And I think it's one of these things that like, how do we learn to work together in this really positive ecosystem of paleontology?

How do we try and get the really rare and important stuff into the hands of scientists and museums?

and museums?

- My only option is to work with people that either own the land or have the leases.

But I'm fine with that, because again, we try and practice what we call citizen science.

what we call citizen science.

- We work with the Field House in Chicago.

We work with the American Museum of Natural History.

So we're really trying to get the fossils that deserve study.

We're really, really trying to get those the attention they deserve.

the attention they deserve.

- We have about 400 specimens on exhibit.

Of those, 26 were found inside the park.

On our land.

The other 300 and some odd all came from outside the Monument, out of these commercial fossil quarries.

out of these commercial fossil quarries.

- Some people say that we don't know exactly what we're doing.

We're not educated.

We don't have any formal education.

People like me actually do care.

We do care about the scientific value that goes into the specimen that we pull out of the ground.

We wanna know this information.

This is our love, this is our passion.

- It's the relationships that you build with scientists that turns out for the benefit of science, that will eventually change that outlook.

- Lance Grandy figured this out quickly along the years.

You're not gonna find the rare stuff unless you're digging the common stuff.

Unless the fossil fish quarries are doing the work and selling the fossil fish, you're not gonna find Tynsky's horse.

[wind blows] [train horn blares] [calm music] - You know, as a museum paleontologist, we always have our ear to the ground about when interesting fossils are found.

I heard that somebody had found a whole perfect horse.

And I bumped into Arvid Aase at a meeting in Seattle.

- "Hey Arvid, is that horse still available?"

- "Hey Arvid, is that horse still available?"

"Yes, it is.

Do you need contact information?"

"Yes, I do."

"Yes, I do."

So I got him contact information.

So I got him contact information.

- I kept thinking, "You know, it would be pretty good to see Jimmy Tynsky's horse here in Washington, DC."

- I had several people interested in it, but I could never make a deal with them.

Between me and the rancher and the people, you know, just never could come to terms.

you know, just never could come to terms.

- The Smithsonian, and that fella, he'd known of it before, had seen it before, and then finally decided, well, it was something to pursue.

- Herb Johnson called me when we started working the deal about the Smithsonian getting it.

He just said, "We have got a couple donors, we're pretty sure that we can purchase this fossil."

[gentle music] [Alex] It was an extraordinary day for Jimmy, I remember it fondly, you know.

It was like it was all his life work actually paid off.

The day that he sold his horse, first thing he did is pay off his house.

first thing he did is pay off his house.

- I was living in a double wide trailer here.

After the horse, we were able to pay the house off.

Me and my wife, you know, we lived a little bit more comfortably than what we would've.

So right after that, it wasn't a year or two after that, that I came down with cancer, so.

You know, it was a good thing I was able to pay off a lot of bills and everything.

to pay off a lot of bills and everything.

- It was a great moment when the crate came here to the museum and we opened up the crate, and that was the first time I'd actually seen the fossil face to face.

[gentle music] Tynsky's horse is the hope diamond of the fossil world.

It's an amazing fossil.

It's an amazing fossil.

And this is an exhibit in which will see five, six million people a year.

And every year, it's different people, so in a decade, we'll see 50 or 60 million people in this room, looking at that fossil.

And that, to me, is a really great tribute to Jimmy Tynsky's tremendous good luck on that one day, and his life time of collecting fossils and the fossils of Wyoming.

[wind blows] - Kemmerer had been really good to us.

Kemmerer is a great town to raise a family in.

Kemmerer is a great town to raise a family in.

The coal mine pretty much kept everybody pretty much employed around here.

They're worried about him closing down, so that's the whole thing, you know.

What's gonna happen to the economy of this town if that ever happens?

if that ever happens?

- Kemmerer has been so tied to the mine for so long.

And the mine is what has provided a living for most of these people around here.

for most of these people around here.

[Narrator] The town of Kemmerer is ground zero for a broader energy transition happening across the United States.

Energy utilities are moving away from coal.

Energy utilities are moving away from coal.

Coal has been at the center of life for over a century in this Wyoming town.

[gentle music] But the Kemmerer community is determined to remain strong.

[upbeat music] ♪ - It's just looking for another boom, and I don't know what type of boom it would take, you know?

you know?

- In South West Wyoming, plans from a company backed by Bill Gates to build a small nuclear power plant are now moving forward.

Terrapower announced this week that Kemmerer, Wyoming will be the first location of the first nuclear power plant using its Natrium technology.

[upbeat music] - There's a nice one.

- There's a nice one.

- The only thing they could do better is promote more tourism to come and actually partake, you know, to dig in the quarry.

and actually partake, you know, to dig in the quarry.

- We need to do that a lot more because this is one of the premiere fossil formations in the entire world.

fossil formations in the entire world.

- Fossil Butte used to be just a wide spot of the road.

With a little trailer.

And then they built a visitor center and expanded.

It's really, it's kind of a destination now.

It's really an awesome place.

It's really an awesome place.

- I've set my ranch in a trust.

It's to be maintained so these private quarries can still lease their quarries, so it can continue in its present state.

so it can continue in its present state.

- I hope everybody can keep working and make a living and enjoy, you know, a good lifestyle.

And enjoy, you know, what they love to do.

And enjoy, you know, what they love to do.

I even go up now and work for my son now, you know.

Just it helps me a lot.

And I love to dig fossils.

I love digging the fossils, so, when I'm not doing the treatment, I go up and dig for him.

I go up and dig for him.

My dad said it's like opening presents.

You never know what you're gonna get.

You never know what you're gonna get.

- I started fossils like, three years ago.

I'm trying to be a football player, but if I don't make that, then fish.

but if I don't make that, then fish.

It's cool just splitting the rock and then finding what you see.

Like, you might not find something on one time.

But then on another time, you might find like, a whole set of things.

a whole set of things.

- When I'm gone, it's... [laughs] it's up to the different generation then.

it's up to the different generation then.

- That's what I like about my job.

Making that discovery first hand.

I watch the children come in.

When I give them a fossil and their eyes light up, that's my inspiration, right there.

- I've always been really interested in science, even from a super young age.

So I've had a lot of help getting here.

And I really wanna be able to share that to more little kids, especially little girls who are thinking about maybe being a paleontologist because they totally can.

because they totally can.

- I understand why fossils are so compelling.

I mean, these are just these extinct monsters of the past.

It's possible you can actually find them.

Not all of them have been found.

The best ones are still waiting to be found.

And just to watch kids bombing round this room looking at this stuff is just, it's a true pleasure.

it's a true pleasure.

This planet really does have a history, and the history informs its future.

And what happens next with people on planet Earth.

And we're part of this story that includes mammoths and dinosaurs and Jimmy Tynsky's horse.

and Jimmy Tynsky's horse.

- There's still crazy, wonderful things are yet to be found.

crazy, wonderful things are yet to be found.

- I love working with the fossils and the people that work with the fossils.

That's fun.

It's an ecosystem here preserving rock.

And then we have all these people that love them too, and it's a great community.

[upbeat music] - You know, I've been doing this for 40 years plus.

I tell people, I wish I'd have got in the business of selling feathers instead of rocks.

'Cause it's hard on your back.

My knees are shot.

I worry about the dust.

The elements are brutal.

The elements are brutal.

And it's getting kind of old.

Even though I still love it, I still...

When you pop open something nice, it's "Wow," you know, that little rush that you get.

And I'll never get over that.

Never.

Never.

When I was young, I did it every night.

But after 40 years, it's like, "Yeah, we can quit early tonight."

[laughs] Is the bar still open?

[laughs] [dramatic music] [dramatic music] [upbeat music] ♪ ♪ - Major funding for this program was provided by a Memorial gift honoring Betty Buckingham Baril, PhD, and her passion for the natural world and science education.

and science education.

The Wyoming Communities Council.

Helping Wyoming take a closer look at life through the humanities.

The Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, because culture matters.

A program of the Wyoming Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources.

Wyoming Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources.

A generous gift from MAS Revocable Trust.

And the Wyoming Public Television Endowment.

And the Wyoming Public Television Endowment.

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Special | 30s | Fossil hunters seek their fortunes in remote western landscapes. (30s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: Special | 3m 29s | Fossil hunters seek their fortunes in remote western landscapes. (3m 29s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Explore scientific discoveries on television's most acclaimed science documentary series.

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

Fossil Country is a local public television program presented by Wyoming PBS