How Leonardo da Vinci Created Narratives in His Paintings

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 6m 37sVideo has Closed Captions

Leonardo da Vinci paints The Virgin on the Rocks and the portrait Lady with an Ermine.

Leonardo da Vinci paints The Virgin on the Rocks – the most complex Madonna image of the entire Renaissance. But, after a disagreement over money, he withheld the painting. Meanwhile, Leonardo forms his own studio in Milan and finally begins getting commissions from Ludovico Sforza, including a portrait of a young woman who had caught his eye Cecilia Gallerani – or Lady with an Ermine.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding for LEONARDO da VINCI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and by...

How Leonardo da Vinci Created Narratives in His Paintings

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 6m 37sVideo has Closed Captions

Leonardo da Vinci paints The Virgin on the Rocks – the most complex Madonna image of the entire Renaissance. But, after a disagreement over money, he withheld the painting. Meanwhile, Leonardo forms his own studio in Milan and finally begins getting commissions from Ludovico Sforza, including a portrait of a young woman who had caught his eye Cecilia Gallerani – or Lady with an Ermine.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipEventually, he formed a partnership with brothers Ambrogio and Evangelista de Predis, who operated a successful local studio.

Together, the 3 artists secured a commission to paint an altarpiece for the chapel of the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception.

The contract-- dated April 25, 1483-- specified that the altarpiece should include an image of the Virgin and Child, flanked by two smaller side panels.

Leonardo was to paint the central panel.

Verdon: Mary, of course, was the most common subject in medieval and Renaissance art.

♪ Here, Mary is Leonardo's focus.

♪ Mary's right hand, which is on the back of John the Baptist, is very tense.

The fingers are pressing into John's back, but the thumb is over his shoulder, and what she's doing is holding him back.

Mary, in the popular theology that Leonardo and everyone at the time knew, already understood her son must one day die, and here, he shows her preventing the prophet of her own son's future death from drawing near to Christ.

Christ, the child at her left, accepts this future death.

Indeed, He's turned to John the Baptist, and He's blessing him.

She's lowering her left hand toward His head, but her hand can never reach her child's head because there's a figure, an angel, kneeling behind her son, and the angel is pointing toward John the Baptist.

Mary, as human mother, knows her son must die but cannot accept that, and so God sends His angel to prevent Mary's instinctive, natural, maternal instinct from avoiding the future Passion.

It is absolutely the most complex Madonna image of the entire Renaissance.

♪ Its complexity lies in a probing effort to understand a deep mystery, which is how, in a woman prepared from all eternity to bear the Son of God, humanity still fully expresses itself.

♪ Narrator: After a disagreement with the monks over money, Leonardo and his partners withheld the painting.

Their dispute would go unresolved for decades.

Bambach: Leonardo will do what Leonardo does, pretty much disregarding what the expectations of the patrons are, and the patrons learned through their enormous frustrations-- and they would get quite angry-- that this was who Leonardo was.

Narrator: Leonardo soon formed his own studio in Milan, where he collaborated on portraits and religious works with assistants and other accomplished masters and offered instruction to eager apprentices.

He started but abandoned a painting of the 4th-century theologian and ascetic Saint Jerome.

He got further with a portrait of a musician, likely Atalante Migliorotti, who had traveled with him to Milan, and Leonardo finally began to get commissions from Ludovico Sforza.

Among them was a portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, the well-educated teenage daughter of a Milanese civil servant who had caught Il Moro's eye and soon after was living in a suite of rooms in his castle.

♪ Kemp: What Leonardo has done is to tell a mini-narrative in this image.

She is holding the ermine, this animal which is symbolic of purity because the ermine was said to prefer to die rather than get dirty, and she is turning away from us, looking, and smiling slightly, so we must imagine the duke is over there.

We're looking at her.

She is looking at the duke.

She is given status by this unseen presence, which is just spectacularly remarkable, given the fact that portraits didn't have narratives in them.

Isaacson: The way her wrist is cocked protectively around the ermine, the way the eyes of the ermine and the eyes of the lady are both glancing in the same direction, and the way the light glints off of her eyes and off the white ermine, it's Leonardo at his best, showing a scene in motion.

The greatest task of the painter is to paint the figure and the intentions of the mind.

He says, "Where there is no life, make it alive."

♪ Speaking Italian: ♪

Early Works of Leonardo da Vinci

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 8m 40s | Leonardo da Vinci’s first commissions are a great way to explore his early painting techniques. (8m 40s)

Video has Closed Captions

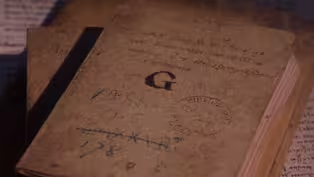

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 8m | Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks provide unique insight into his mind, knowledge and discoveries. (8m)

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 12m 8s | In the early 1490s, Leonardo da Vinci tackled his most ambitious work yet – The Last Supper. (12m 8s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: 11/18/2024 | 1m 10s | Explore one of humankind’s most curious and innovative minds. (1m 10s)

The Vitruvian Man and Leonardo da Vinci's Anatomical Studies

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 8m 2s | Leonardo da Vinci studied anatomy to gain a deeper knowledge of how the body worked. (8m 2s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Corporate funding for LEONARDO da VINCI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and by...